The words “Made in China” have become ubiquitous on clothing labels and electronic devices. Are these same three words proof, too, of an enormous loss of American jobs to the Chinese labor force? Or are they evidence greater still, of U.S. dependency on China?

Much of the debate surrounding the U.S.-China relationship has accused China of depleting employment in America. But the same time, it is crucial to consider other less-championed viewpoints. For example, how many jobs has China created for the United States? How dependent is the American economy truly on China?

Probably much more so than one would think.

With the People’s Republic of China funneling upwards of a billion U.S. dollars into the States everyday, the existing trade surplus of US$1.4 trillion and rising reveals an enormous economic imbalance, a gap that shows no sign of receding with the continual Chinese purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds.

As James Fallows illustrated earlier this year in

The Atlantic, every American has borrowed approximately US$4000 from somebody in China. When put this way, it’s easy to understand how China has funded the American lifestyle, providing the US government the money to spend considerably more than it could otherwise afford. Another way to look at it: the Chinese people are not living as well as they could be. With China’s savings rate at an astounding 50 percent, most of it goes towards savings in the form of U.S. Treasury notes.

What happens is a default procedure circulating U.S. dollars that go into China back out and into the American money supply. As Fallows described, after a factory or company in China trades its incoming dollars for RMB at its local bank, that bank must submit the foreign currency to the People’s Bank of China – think the Chinese version of the U.S. Federal Reserve system. The PBOC is also ordained to pass the money along as well, to the State Administration for Foreign Exchange. For the most part, SAFE decides that the dollars will get the most return as investment in U.S. Treasury bonds which is where they go and from where they can easily become incoming revenue for Chinese businesses again.

This flow of economic wealth characterizes China’s preferred path to growth. Why has the country adopted such operations? The answer involves an acutely cautious course of action designed to propel intense economic development. In effect, the central government simultaneously wants to safeguard against aggravated tensions among its social classes, generate increased employment opportunities for its people, and prevent possibly ruinous hyperinflation of the Chinese yuan. Holding American reserves thus keeps these intentions alive while also protecting to a certain extent the dollar, which acts as the clasp that holds Beijing’s strategy in place.

As for how long China will adhere to this approach is of course, a hot topic of discussion and speculation. The country is in no hurry to abandon the dollar by any means. Although the United States in retrospect most likely would have preferred not to be in the position it is today—this dependent upon Chinese subsidies and burdened by such a large trade deficit—at this point, it makes the most sense for America to ponder the future.

The China market is as alluring as ever. Increasingly, U.S. companies see how that their profit-making potential in China is not only growing but also greater than it is in America. At the same time, gaining access to Chinese markets, which used to be a top challenge for American firms interested in doing business in China, has become much easier.

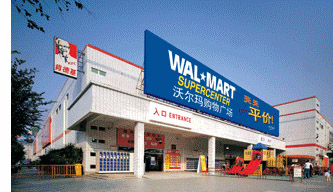

Restrictions have loosened on Beijing’s end, and U.S. companies are finding less and less reason not to enter the Chinese market. The world’s largest private employer, Wal-Mart Stores Inc., is a prime example. It has been utilizing the advantages China can provide for buying from China for quite some time. According to the consumer watchdog

Wal-Mart Watch, the chain obtains approximately 80 percent of its supply from China. With its “everyday low price” motto, the American public corporation owns a global phenomenon of over 6,000 retail outlets worldwide.

Although its profits in China comprise a small percentage of its total earnings, Wal-Mart nevertheless is aggressively expanding on the mainland as it looks to capitalize on a rapidly growing Chinese middle class. Beijing, too, has made it easier for expanded operations by foreign retailers since Wal-Mart moved into China in 1996.

In December 2007, Wal-Mart announced plans to open its 100th store in China, continuing its national development rate of more than 30 percent annually. For the most part, its success has been embraced as a grand gain for both the United States and China. As Carlos M. Gutierrez, the U.S. commerce secretary said, “Wal-Mart’s expansion benefits millions of US shareholders, creates valuable jobs in the United States and creates new jobs for Chinese.”

Wal-Mart’s ability to keep prices low has helped keep it going strong even in the midst of a slowing American economy.

Pravda reported that price-conscious American shoppers flocking to the chain have helped it take back some of its market share from Target Corp.

As such, China appears to be an increasingly enticing playground for American enterprise. The realm of outsourcing also speaks to the growing interest. As reported by BDO Seidman’s

2008 Technology Outlook Survey, while the most common location currently for outsourcing is India followed by Southeast Asia, a U.S. technology companies have indicated that China could very well surpass Southeast Asia in the future.

China is still one of today’s most appealing outsourcing opportunities. A well-functioning national infrastructure coupled with a stable government provides a solid base for foreign-owned business. In addition, the large labor force with an emerging order of western-educated leaders can help ease the transition of multinationals into the Chinese market, as do the numerous support industries that cater to any need or help desired.

Outsourcing is not a one-way street however, and many foreign corporations have transferred their operations into the United States. Whereas about 15 million jobs have been lost each year for the past 10 years or so, 17 million have been created each year, too, according to the

National Center for Policy Analysis. A sizable portion of these jobs have come from foreign companies setting up business in the United States.

Two examples from China which have done so are Haier, an appliance manufacturer, and Lenovo, the computer manufacturer. Besides branding, management, and other potentially expected benefits, the weakening dollar and America’s status as one of the world’s largest consumers have made it more attractive to foreign companies.

Most recently, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. has said that he would pressure the Chinese to open their economy up even more with regard to “the concerns of American companies that China’s investment regulations are opaque and seem in many ways to be designed to favor China’s ‘national champions.’” Paulson suggests that U.S. competition is being shut out to a certain extent.

But America need not fear Chinese practices. The RMB has steadily appreciated—almost 20 percent since its revaluation in July 2005. Consequently, the degree to which exports to China have increased has surpassed the rate at which imports from China have risen, and the U.S. trade deficit is on the decline from its all-time high of US $256.2 billion last year.

Fallows argues that, in various ways, China as the world’s emerging superpower should not be as threatening as it has been publicized to be. The country is unquestionably transforming itself and in the process strengthening itself but it is doing so by building off of its global connections. For China to bring about the downfall of any other state, and especially that of the United States., would be a case of post-Cold-War mutual assured destruction.

If anything, America should worry about a China in this century that proves unable to sustain its rapid expansion or worse, suffers a breakdown for therein, lies the greatest threat of all and for all parties involved.